In Roy Courtnall’s book, Making Master Guitars, there’s an interview with José Romanillos in which he talked about some of techniques he uses. To attach the ribs to the foot of the neck, he prefers a wedged joint over the usual 2mm wide slot cut at the 12th fret line. Apparently, he got the idea from seeing such a joint in a 17th or 18th century French guitar. He gives some rudimentary instructions about how to make it:

‘You cut a wide tapering slot, then fit the rib tight up against the front end. Then you drive a wedge down, which matches the taper exactly. It is very strong.’

Well, I haven’t had any problems with strength of the joint when the ribs are housed in conventional narrow slots. But I’ve never found it easy to cut these slots to exactly the right width with a hand saw. If you want to do it with a single cut, you need to adjust the set of a back saw so that it cuts a kerf 2mm wide. Quite apart from the fact that it’s hard to do this without breaking the teeth, it makes the saw almost useless for any other purpose. The alternative is to do it by making two cuts. After the first cut, you can place a piece of plastic or plywood in the kerf to guide the saw for the second cut. But it’s not a very satisfactory solution because it’s too easy to cut into the plastic or wood and end up with a slot that’s too narrow near the bottom. You can get around that problem by substituting a sheet of metal, such as a cabinet scraper, but it doesn’t do the saw much good. Things get even more difficult if you want the slot to be 2.5 or 3.0mm wide to accommodate laminated ribs.

So I was interested to learn about Romanillos’ wedge technique and decided to try it out in the guitar that I’m making at the moment, which does have laminated ribs – zebrano lined with maple with a finished thickness of about 3mm.

The 2 photographs below show the wide tapering slots cut and chiselled out in the foot of the neck before the heel has been shaped.

Here, I’ve roughly shaped the heel and lower part of the neck.

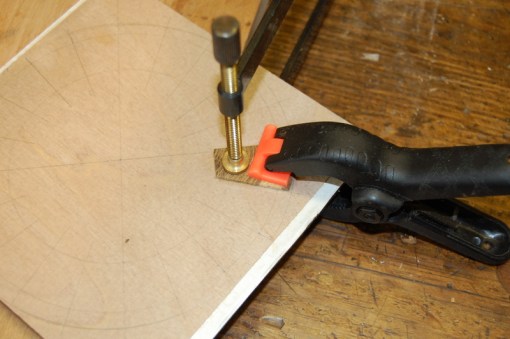

Then I cut the wedges and adjusted them to fit. Obviously, it’s particularly important that they draw everything up tight before the narrow end of the wedge reaches the soundboard end of the slot. I deliberately made them too long initially to give plenty of room for error.

This is a dry run before gluing to make sure that everything fits perfectly. I discovered that another advantage of making the wedges too long at the beginning was that it provided something to grip when wriggling them out.

And this is the finished joint, glued and cleaned up. As you can see, I’ve already started attaching the ribs to the soundboard with tentellones.

Altogether, this turned out to be a useful experiment. The wide slot presented no problems to saw or chisel out. Indeed, it was significantly easier than cutting the conventional narrow slot. There’s a bit of extra time and trouble preparing the wedges but, as long as you have the right jig (see here) it’s not difficult. Gluing up was easy: plenty of room to coat all the surfaces before putting them together and sliding in the wedge. A couple of taps with a light hammer and it’s done. I’m fairly sure that I shall be using this technique again.