James Gordon, an engineer, materials scientist and naval architect, wrote two books that I highly recommend. I was about to write …to woodworkers but, actually, I highly recommend them to anyone who has the slightest interest in buildings, ships, aeroplanes or other artefacts of the ancient and modern world. My copies have been read and consulted so often that they’re falling apart. They are The New Science of Strong Materials or Why you don’t fall through the floor (first published in 1968, but still in print: ISBN-13: 978-0140135978) and Structures or Why things don’t fall down (first published in 1978 and also still in print: ISBN-13: 978-0140136289). Both are written for a non-expert readership and there’s very little algebra or mathematics. They’re fun too: Gordon writes clearly, wears his learning lightly and the text is spiced by his whimsical sense of humour.

The New Science of Strong Materials has many interesting things to say about the properties of wood and why it’s such a wonderful and versatile material. There’s stuff about how wood is able to cope with stress concentrations and limit crack propagation, about how glues work, the distribution of stress in a glued joint, and many other things of deep background interest, if not of immediate practical significance, to people who use timber.

The second book, Structures, is equally gripping. It explains how medieval masons got gothic cathedrals to stay standing, why blackbirds find it as much of a struggle to pull short worms out of a lawn as long ones, and the reason that eggs are easier to break from the inside than the outside. Of more direct relevance to woodworkers is its straightforward account of how beams work – which means that, if you’re thinking of making something like a bed or a bookcase, you can calculate whether the dimensions of the boards that you’re planning to use are up to the load they will have to bear, which is obviously useful in making sure that your structure is strong and stiff enough.

Slightly less obviously, it’s also helpful in giving you the confidence to pare down the amount of material that you might otherwise have used. A common fault of amateur woodworkers, it seems to me, is that when designing and making something small, they tend to use wood that is far thicker than it needs to be, which means that the finished object looks heavy and clumsy. Conversely, when making something large, they tend to use wood that is less thick than it should be, and the structure often ends up rickety and unstable.

Knowing a bit about beams might also be advantageous for guitar and violin makers. Here’s an example: take a strut or harmonic bar, rectangular in section, that you’re intending to glue onto the soundboard of a guitar. How is its stiffness related to its shape and its dimensions? What’s the best way to maximise stiffness while minimising weight?

Elementary beam theory tells us that, for a given length, stiffness is proportional to the width of the beam and to the cube of its depth. So if you double the width, the stiffness also doubles. On the other hand, doubling the depth, increases stiffness 8 times. If stiffness is what you’re after, it’s a lot more efficient to make the bar deeper than it is to make it wider.

This cubic relation between depth and stiffness could be something worth keeping in mind when planing down soundboard braces after they’ve been glued. If a brace is, say, 6 mm high to start with, planing it down by 1.5 mm to a height of 4.5mm will reduce its stiffness to less than a half of what it was originally. And shaping the braces to make them triangular or arched in cross section also reduces their stiffness considerably.

Mind you, like so many attempts to understand guitars from a scientific point of view, things rapidly get complicated. A structural engineer with whom I discussed the matter agreed with what I’ve just said about the depth of the beam being a powerful determinant of its stiffness. But he pointed out that where a beam is an integral part of a structure, the stiffening effect is much greater than you would guess from calculations that assume the beam is simply supported at its ends. This is certainly the case of guitars, where the braces are glued to the soundboard along their entire length and clearly count as an integral part of the soundboard structure. In such circumstances, he explained, the overall stiffening effect provided by multiple braces will be large and might well overwhelm the influence of the stiffness of any individual brace.

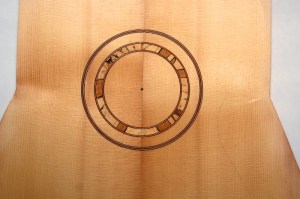

I thought that this was a very interesting idea and that it might begin to explain why so many different bracing systems work remarkably well. In Roy Courtnall’s book, Making Master Guitars, he give plans of soundboard strutting taken from guitars by a number of famous makers. Superficially they’re fairly similar, all being based on a fan-like pattern of 5, 7 or 9 struts. There are minor variations, of course. Some are slightly asymmetrical, some have bridge plates and closing bars and so on. But the biggest differences lie in the dimensions of the braces. Courtnall shows a soundboard by Ignacio Fleta that has 9 fan struts and 2 closing bars which are 6mm in depth and an upper diagonal bar 15mm depth. By contrast, a soundboard of similar size by Santos Hernández has only 7 fan struts 3.5mm in depth and triangular in section. Applying simple beam theory would lead one to guess that Fleta’s bracing would add more than 10 times the stiffness that Hernández’s does. But perhaps that’s a misleading way to look at it. If one were able to measure or calculate the stiffness of the whole structure, by which I mean the soundboard with its bracing when attached to the ribs, the difference in stiffness between them might turn out to be much less.

It’s a question that might be tackled by finite element analysis and I’d be glad to hear from anyone who has tried. Some work along these lines has been done on modelling a steel string guitar, which at least shows that the approach is feasible.

In the meantime, without a proper theory, we’re stuck with the primitive method of trial and error. Below are some of the bracing patterns that I’ve experimented with. All produced decent sounding instruments but I’d be at a loss if I were asked which particular tonal characteristics were produced by each of the different patterns. It may be that William Cumpiano was right when he wrote (in his book, Guitarmaking, Tradition and Technology):

Specific elements of brace design, in and of themselves, are not all that important. One has only to look at the myriad designs employed on great guitars to recognise that there is no design secret that will unlock the door to world-class consistency.

All this means that I’ve been arguing in a circle. Perhaps the conclusion is that beam theory isn’t very useful to guitar makers after all. Still, if you take up the recommendation to get hold of Gordon’s books, the time you’ve spent reading this post won’t have been entirely wasted.